Radostin Vazov

University of National and World Economy

https://doi.org/10.53656/his2025-6s-1-fai

Abstract. This article analyzes how Mount Athos became a durable economic actor in the Middle Byzantine period (9th–12th centuries). Building on translated monastic foundation documents and Athonite acts alongside recent economic and institutional historiography, I examine (a) imperial patronage and fiscal immunities; (b) land acquisition and the metochia network; (c) resource management, labor, and market integration. Methodologically, the study combines documentary analysis (typika, chrysobulls, praktika) with an institutional lens on property rights and exemptions (exkousiai), situating the Athonite koinon at the intersection of Orthodox canon law and imperial governance. The findings clarify a post‑Iconoclastic trajectory: from state protection to endowed, tax‑privileged estates that sustained large cenobitic houses (Lavra, Iviron, Vatopedi). Athonite monasteries consolidated land by donation and purchase, administered dependent peasants with comparatively mild dues, and regularly exchanged surpluses (grain, wine, oil, timber) with regional markets, especially Thessalonica, while importing non‑produced essentials. Far from a contradiction, Athos’ “sacred economy” was a corporate, rule‑bound system that reconciled ascetic ideals with prudent resource management. The article refines our understanding of Athos as a fiscally semi‑autonomous enclave whose endurance depended on secure rights, exempt status, and diversified estates rather than isolation.

Keywords: Byzantine monastic economy; Mount Athos; metochia; tax exemptions; Middle Byzantine period.

1. Introduction

Mount Athos evolved in the Middle Byzantine era from eremitic clusters into a coordinated commonwealth (koinon) of monasteries with a presiding protos. Its economic rise is inseparable from the post‑Iconoclastic consolidation of Orthodoxy and renewed imperial patronage visible from the ninth century (under Michael III) onward (Kaplan 1992; Angold 1995). Scholars have emphasized the apparent paradox of cenobites who renounced private property yet managed large corporate estates; the paradox dissolves once one foregrounds institutions legal immunities, property rights, documentary governance and the Athonite koinon’s status within the Byzantine polity (Harvey 1996; Laiou & Morrisson 2007; Laiou (ed.) 2002).

Aim and scope. This article identifies the foundations (rights, endowments, immunities) enabling Athos’ economy and the operational mechanisms (estate management, labor, exchange) through which monasteries converted privileges into durable provisioning between the 9th and 12th centuries.

Approach and sources. The analysis integrates (1) translated monastic charters/typika and Athonite actes1, (2) synthetic economic history (EHB 2002; Laiou & Morrisson 2007), and (3) focused case studies on monastic property, fiscal practice, and social relations (Morris 1976; Smyrlis 2006; Mullett & Kirby 1994/1997)2.

2. Imperial Patronage and Land Endowments

The economic rise of Athonite monasteries was rooted in imperial patronage from the very beginning. As early as the late 9th century, the Byzantine state took measures to protect the nascent monastic community on Athos. Notably, Emperor Basil I issued an edict in 8833 prohibiting the herdsmen of nearby communities (the enoria of Hierissos) from bringing livestock onto Athos (Harvey 1990). This decree, one of the earliest official interventions, effectively set aside the peninsula for monastic use, preventing external exploitation of its lands and resources. Such protection acknowledged the presence of anchorites on Athos and can be seen as the foundation for Athos’s later autonomy. By shielding the Holy Mountain from encroachment, the state created a sanctuary where monastic settlements could take root in an undisturbed environment.

In the early 10th century, Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos began providing an annual stipend (roga) to the monks of Athos (Thomas, Hero 2001). According to monastic documents, this pension was approximately three pounds of gold per year, distributed among the scattered hermitages (Thomas, Hero 2001). Such direct funding helped sustain the ascetic population, though resources remained modest at this stage. A transformative moment came in 963, when Athanasius the Athonite founded the Great Lavra Monastery with the backing of Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas (Obolensky 1988). Athanasius, a former patron of the influential Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople, obtained unprecedented support from his imperial friend. Nikephoros II provided lavish financial aid doubling the annual Athos stipend for Athanasius’s benefit and donated large sums and materials to build the Lavra complex. Imperial gold paid for churches, storehouses, fortifications, and the initial communal refectory and dormitories. By one account, Athanasius secured six pounds of gold annually for his monastery (twice the previous Athonite fund) and even convinced the emperor to raise the general Athonite roga to seven pounds, thus spreading benefits to other monks. This infusion of cash allowed Lavra to support about 80 monks in its first years (Thomas, Hero 2001).

Throughout the 11th century, successive emperors continued to enrich Athos, though often shifting from cash stipends to land grants. The reasoning was pragmatic: instead of burdening the state treasury with annual outlays, the emperor could grant a monastery a tract of imperial land or a share of tax revenues from certain villages, making the institution self-financing. One pivotal benefactor was Emperor Basil II (r. 976–1025), who, after consolidating Byzantine rule in the Balkans, is said to have endowed Athonite monasteries (especially the Georgian monastery of Iviron) with extensive lands in Macedonia and other regions (Thomas, Hero 2001). While exact details of Basil II’s donations are sparse, later documents allude to estates given “before 985” to Vatopedi and others. For example, Vatopedi Monastery already held a village in the Serres region by Basil’s time. Over the next centuries, that village Semaltos and its inhabitants would be confirmed as Vatopedi’s property by various rulers including a Bulgarian tsar’s chrysobull in 1230, which reiterates the complete fiscal immunity of Semaltos under monastic control. Such continuities suggest an initial grant in the Byzantine period. Basil II’s reign likely also brought direct tax privileges: he is credited with exempting the Athonite houses from the allelengyon, a short-lived tax that obligated the wealthy to cover arrears of poorer taxpayers) and from certain military levies. Moreover, Basil II increased Athos’s prestige by visiting and patronizing Iviron and Lavra; according to later tradition, he deposited the celebrated Vladimir Icon at Vatopedi as a gift. The cumulative effect of 10th – 11th-century imperial patronage was the creation of a vast monastic land endowment. By 1045, the Great Lavra had grown to shelter over 700 monks (Alan 1990), a number far beyond the original endowment of gold, indicating that extensive landholdings were now sustaining the community. Indeed, one source notes that by the late 10th century over two dozen monasteries had been founded on Athos (Alan 1990), many of them sponsored by princes or senior officials of the empire. The three “great” monasteries Lavra, Vatopedi, and Iviron spearheaded the expansion and received the lion’s share of early imperial favors. But smaller foundations also benefited as the emperors, as well as aristocratic patrons, vied to endow chapels and monasteries for the salvation of their souls. Land grants, whether imperial or private, typically came with ektenesis documents (donation charters) specifying the properties and the tax exemptions attached. These charters were then confirmed by imperial chrysobulls to ensure legal validity.

- Land Tenure and the Metochia Network

At the core of Athos’s economic system was control of land. The term metochion (pl. metochia) denotes a dependent monastic estate, often far removed from the Holy Mountain itself. From the 10th century onward, Athonite monasteries amassed metochia of various types: agricultural villages, vineyards, pastures, forests, mills, and urban houses. These estates came into monastic possession through several channels. Donations were paramount – pious emperors, nobles, and officials donated family lands or territories recently conquered. For instance, around 1080 the scholar and statesman Gregory Pakourianos donated extensive estates in Thrace and Bulgaria to found his own monastery (Bachkovo/Petritzos), and also gave some lands to Iviron (Laiou, Morrisson 2007). Similarly, the pronoia holder Eustathios Boilas in 11th-century Asia Minor willed part of his estates to the Iviron monastery, as attested by his testament. Athonite houses also purchased land outright or received it in exchange. The Acts of the Athonite monasteries (preserved in the Archives of Mount Athos series) contain numerous deeds of sale from the 11th–12th centuries, indicating that monasteries invested surplus funds to buy neighboring plots and entire villages when available. According to Laiou and Morrisson, monasteries actively tried to consolidate contiguous lands acquiring fields adjacent to their existing metochia to form larger, more efficient estates (Laiou, Morrisson 2007).

Monasteries also expanded their holdings through imperial grants. In some cases, the emperor would grant a monastery fiscal right over a village (for instance, the right to collect the land tax from that village for the monastery’s benefit). In other cases, entire strips of land, often in frontier or undeveloped zones, were granted to encourage monastic settlement and cultivation. (Smyrlis 2002). A striking early example is the island of Amouliani near Athos, given to Vatopedi, traditionally by Emperor John Tzimiskes4, as a fishing station and agricultural outpost. (Smyrlis 2002) By cultivating donated lands and drawing in peasant settlers often paroikoi, or dependent tenant farmers, the Athonite monasteries created productive agrarian enclaves that generated food and income. These metochia were the economic lifeline of the cloister: grain from the fields, grapes from the vineyards, timber from forests, and herds from pastures all flowed from the hinterlands to the monastic storehouses on Athos.

By the 12th century, Athos had developed a quasi-corporate estate management system. The pronoia system under which emperors granted individuals the right to tax or revenue from lands largely spared Athos during this period; while many secular estates were broken up into pronoias for soldiers, monastic estates were kept intact, due to the sanctity of church property and the influential backing of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. One exception was the practice of charistikion in the 11th century, where monasteries, especially smaller ones, were placed under the tutelage of lay charistike holders who would administer the monastery’s assets in exchange for a share of revenue. The Athonite monasteries strongly resisted charistikion. There is scant evidence of any Athonite house being subjected to a lay administrator indeed the whole point of Athos’s autonomy was to avoid such secular intrusion. A 12th century council eventually condemned abuses of the charistikion system, aligning with Athos’s stance. Thus, unlike some urban monasteries, the Athonite houses retained direct control over their estates rather than seeing them managed for profit by outsiders.

Tensions sometimes arose with neighboring villagers over grazing rights. For instance, a dispute in the 940s saw the villagers of Hierissos contest the extent of Athonite land available for their herds (Alan 1990). Such conflicts underscore how monasteries, by expanding their landed domain, could encroach on local communities. In most cases, imperial authority sided with the monasteries, as seen by the issuance of boundary rulings and enforcement of monastic rights. Over time, Athos consolidated a contiguous territory on the peninsula itself essentially the whole peninsula became monastic property, with no lay villages allowed and a distributed network off the peninsula. The metochia network was the backbone of Athos’s wealth generation, ensuring a flow of natural resources and agrarian surplus from the Byzantine countryside into the monastic economy.

4. Taxation Privileges and Fiscal Exemptions

One of the most critical economic advantages enjoyed by Athonite monasteries was their extensive tax exemptions. Byzantine fiscal practice typically dictated that landowners whether secular or ecclesiastical were liable for land tax and various surcharges on the productive activity of their estates. However, from an early date Athos secured relief from these burdens. As noted, Emperor John Tzimiskes’s 972 charter explicitly freed Athos from virtually all state imposts. This was not an isolated generosity: it set a precedent for subsequent chrysobulls. In Byzantine legal terminology, Athonite monasteries were often granted “exkousiai” (privileges of exemption), meaning that their properties and dependents were exempt from taxation and from the interventions of tax officials. Over the 11th and 12th centuries, emperors issued numerous renewal chrysobulls to the major monasteries, itemizing the exemptions. Typically included were: the land tax (ensatikon or zeugaratikon on peasant plots), the kapnikon (hearth tax on households), kommerkiakon (customs dues on goods, especially relevant if the monastery transported goods by sea), kommerkion/komodion (market tax), telos sitos (grain levy), dekate (tithe on produce), and corvée labor obligations (angareia).

For example, a chrysobull of Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos in 1045 issued after a dispute between hermits and cenobitic monasteries reaffirmed that while certain economic activities of monks should be limited (to preserve spiritual focus), the large monasteries like Lavra and Vatopedi were permitted to maintain the resources necessary for their size, and that included continuing their tax-free status (Thomas & Hero 2001). Constantine IX’s typikon, in effect a law for Athos, struck a compromise: it acknowledged complaints that some monasteries were becoming too “worldly” in their pursuit of wealth, but pragmatically allowed them exceptions such as owning transport boats or more draft animals, given their greater needs (Thomas & Hero 2001). In return, the monasteries remained loyal to the emperor and prayerfully supportive of the imperial house. The balance of exchange was clear: the emperor gave tax immunity; the monasteries gave spiritual intercession and upheld the Orthodox order on the frontier.

The scope of Athonite exemptions was extraordinary. In practice, if a monastery owned a village outright, all the paroikoi (dependent peasants) in that village paid their taxes to the monastery’s treasury rather than the state, or they were entirely absolved of taxes, with the monastery assuming any necessary payments to the state in a lump sum which often, by privilege, was zero or a nominal amount. A concrete case is seen in the chrysobull of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos to the monastery of Chilandar though slightly post-1200, its conditions reflect earlier norms: the emperor exempted Chilandar’s estates from the kapnikon and agriogrammon taxes and from the duty of providing soldiers or horses, stating that “none of the tax officials shall trouble or levy anything” on those lands. For the Middle Byzantine period, such exemptions meant monasteries were effectively tax shelters. Monastic landlords could often accumulate surplus because they did not owe the usual fraction to the fisc. This led to occasional tension with the government’s need for revenue. In 934, Romanos I had actually legislated against excessive land accumulation by the Church, recognizing the risk to the tax base (Laiou & Morrisson 2007). His Novel of 934 forbade further land gifts to monasteries after a famine, to prevent wealth from concentrating in tax-exempt hands5. However, those laws were not strictly enforced on Athos thanks to its special status and imperial favor.

The economic impact of these taxation privileges cannot be overstated. They allowed Athonite monasteries to reinvest agricultural surplus into their own infrastructure building new churches, fortifying monastic compounds, expanding charitable activities rather than losing wealth to taxation. One might consider it a diversion of public revenue to sacred use. Critics occasionally arose, typically bureaucrats or reformist emperors, who pointed out that too many “dead hands” (the monasteries) held land that could otherwise fill state coffers. For instance, Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos (1183 – 1185) briefly sought to reverse some donations, but his reign was short-lived. On the whole, the political consensus held that Athos’s role in church and society justified its privileged status. Athonite abbots often cultivated personal relationships with emperors, emphasizing their monasteries’ prayers for the imperial family and hospitality toward imperial dignitaries, which helped renew privileges. By 1200, the Athonite monasteries were largely self-governing fiscal enclaves, contributing relatively little in taxes to Constantinople but, in return, assuming local responsibilities, maintaining roads, and providing charity to the poor in their regions. This model illustrates the intertwined interests of church and state in Byzantium: emperors exchanged a measure of revenue for the political and spiritual benefits of strong monasteries that guarded Orthodoxy’s frontier and commemorated imperial benefactors in perpetuity.

5. Resource Management, Trade, and Market Activity

Despite enjoying land and exemptions, Athonite monasteries could not be economically autarkic; they had to engage with the broader market to thrive. Primary production from their estates provided most necessities, but not all. The monasteries, therefore, developed systems to manage resources efficiently and trade surpluses when advantageous.

Within each monastery, a designated officer, often the economos or sakellarios, was in charge of overseeing agricultural production and storage. These officials kept inventories of grain, wine, oil, and other staples produced by the monastery’s metochia. They aimed first to meet the monastery’s own consumption needs feeding the resident monks, novices, lay servants, and the steady stream of pilgrims or poor who received alms at the gate. Athos was famous for its hospitality; even in the 12th century, foreign pilgrims, like the Russian igumen Daniil, wrote of the free lodging and meals offered by the monasteries. To support this, the monasteries had to maintain granaries, cellars, and flocks sufficient to meet year-round demand and to provide emergency reserves. For instance, the Great Lavra undertook a major irrigation project in the 11th century, constructing canals to convey water from the heights of Mount Athos to its gardens and orchards (Harvey 1990). According to its hagiographer, Athanasius the Athonite engineered these works to ensure a reliable food supply even during dry summers. Other monasteries similarly improved their estates with mills, terraced vineyards, and fish ponds. The Kosmosoteira monastery in Thrace (founded 1152) had a typikon detailing the numerous mills and estates endowed for its support (Thomas & Hero 2001), reflecting how monastic founders strategically allocated resource-generating assets to sustain the community.

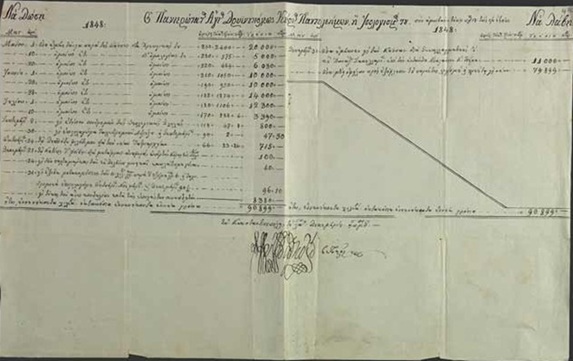

It is important to note that Athos’s market involvement did not equate to profit orientation in the modern sense. Monasteries sold goods not to enrich individuals, but to cover expenses and fund charitable works. Surpluses often went to almsgiving feeding the poor at monastery gates or ransoming captive Orthodox prisoners with collected funds. In some cases, however, the line blurred: critics occasionally accused monasteries of hoarding wealth. Yet sources also highlight how monasteries struggled in lean times; a poor harvest on their lands could force them to buy grain at high prices to feed their monks. This was seen during certain 12th-century droughts when Athos petitioned for relief. The flexibility to trade both ways (sell in good years, buy in bad years) was thus essential for survival. Athonite financial ledgers from much later (Ottoman times) show meticulous accounting for such transactions, implying a longstanding tradition of careful economic management. This proto-managerial approach helped Athos weather the larger Byzantine economic fluctuations, including the 12th-century expansion and the subsequent upheavals around 1204.

Source: Personal Archive. Accounting document Simono Petra Monastery 1848

In summary, Athonite monasteries of the Middle Byzantine era were integrated into regional commerce to a notable degree. They leveraged their tax-exempt status and production capabilities to become net contributors to trade flows – exporting surpluses and participating in import consumption. Their estates functioned much like those of secular magnates, but with the crucial difference that profits were plowed back into religious and communal purposes. This economic acumen, often underappreciated, was a key factor in Athos’s sustained growth. As Laiou succinctly observes, monasteries “sold their production… and purchased what they did not produce,” meaning they were anything but closed economies (Laiou & Morrisson 2007). Athos demonstrates the medieval principle that even ostensibly otherworldly institutions had to master worldly skills to endure.

6. Labor and Administration within the Monasteries

The operation of Athos’s economic system depended not only on land and privilege but also on human organization the labor force and administrative structures that actually tilled the fields, managed accounts, and maintained infrastructure. Here, we see the Athonite economy functioning on two levels: the monastic community itself, with monks and lay brothers working within and around the cloister, and the paroikoi, or lay dependents. Both groups were integral to the production process, governed by hierarchical and ethical norms distinctive to monastic management.

Inside the monasteries, labor was idealized as a form of ascetic obedience. The Benedictine motto “ora et labora” (pray and work) had parallels in Eastern monastic rules. Athanasius of Athos in his Typikon (late 10th c.) prescribed that all able-bodied monks participate in communal work whether in baking bread, working in the gardens, or other tasks under the supervision of the abbot (hegoumenos) (Thomas & Hero 2001). Athanasios himself famously labored alongside his brethren, leading by example. This ethos ensured that basic monastery needs (food preparation, routine maintenance) were met without entirely relying on hired labor.

Administratively, each monastery kept records of its estates. This indicates an advanced level of bureaucracy: officials known as epitropoi, or overseers, were appointed to manage each metochion. These could be trusted monks or, at times, lay employees of the monastery. They reported annually to the monastery’s central administration, providing accounts of the produce gathered and expenses incurred. The primary sources, such as the Praktikon of 1104 for Iviron, reveal details, including how many vines or trees each peasant tended, which implies the monastery’s concern with productivity and the fair assessment of dues.

In conclusion, the labor structure of Athos in the Middle Byzantine era was a blend of ascetic communalism and estate lordship. Monks labored in prayer and necessary tasks, demonstrating that holy life was not idleness. Peasant tenants labored on monastic land, generally under fair conditions and lightened imposts due to the monasteries’ tax privileges. The administrative apparatus, from detailed record keeping to hierarchical oversight, ensured that a sound economic footing supported the spiritual mission. Internal discipline was as crucial as imperial charters in enabling Athos to survive crises. When the Fourth Crusade disrupted Byzantium in 1204, Athos managed to endure relatively unscathed; its self-sufficient network and dependable internal organization meant that, even cut off temporarily from imperial support, the monasteries fed themselves and upheld order, whereas many state-dependent institutions collapsed. Such resilience speaks to the robustness of the economic mechanisms developed in the Middle Byzantine period.

Conclusion

By the close of the 12th century, the monastic republic of Mount Athos stood as a unique example of a medieval religious commonwealth sustained by astute economic management. In this article, we have traced how the Athonite monasteries, over the Middle Byzantine era, built a thriving economic system on foundations of land, privilege, and piety. Several conclusions emerge from this study. First, imperial patronage was indispensable in the early growth of Athos: without the generous land grants, cash endowments, and sweeping tax exemptions conferred by emperors from Basil I to the Komnenoi, the monasteries could not have accumulated their vast resource base or enjoyed the autonomy that allowed them to innovate economically. The symbiosis of church and state in Byzantium enabled a remote monastic community to become a significant landholder across the empire.

Second, the Athonite monasteries proved to be capable and prudent stewards of the wealth entrusted to them. They developed a metochia network that not only supplied their immediate needs but also generated surplus for investment and charity. Utilizing tools like written charters, audits, and delegated estate managers, they administered far-flung properties with a level of organization comparable to contemporary feudal estates or even modern corporations in embryo. While the analogy should not be overstated, Athos did exhibit a form of centralized management over decentralized assets, a “proto-holding” structure wherein the monastery as headquarters controlled numerous satellite units (farms, mills, etc.) through a defined chain of command.

Third, Athos’s experience underscores that spiritual and economic motives were not mutually exclusive in the medieval Orthodox world. The Athonite monks engaged in commerce and profited from landownership not for personal gain, but to sustain a way of life dedicated to worship. The wealth they amassed was used to build churches, feed the poor, copy manuscripts, and ransom captives. In an era of frequent warfare and instability, the monasteries functioned as islands of stability their economic strength underwrote cultural and charitable endeavors that benefited the broader society.

Finally, this study highlights the adaptability and resilience of the Athonite economic model. Through prudent management and the sanctity attached to their imperial guarantees, the monasteries weathered challenges that might have broken lesser institutions. They survived the debts and demands occasionally imposed by emperors, navigated the tension between spiritual ideals and practical needs, and even managed transitions of political power (e.g. when Byzantine authority waned, Athos secured protection from Latin and later Slavic rulers, often by emphasizing the continuity of the privileges first granted in the Middle Byzantine period. In essence, the foundations laid in the 9th–12th centuries of legal autonomy, diversified income, and disciplined administration ensured that Athos could endure the upheavals of the 13th century and beyond. The Middle Byzantine Athos thus serves as a case study in how religious institutions can attain economic might while ostensibly renouncing worldly pursuits. Far from being an economic backwater, Mount Athos in this period was a dynamic participant in the Byzantine economy, demonstrating that faith and finances, when carefully balanced, could reinforce each other’s longevity.

In conclusion, the Athonite monasteries of the Middle Byzantine era exemplified a successful melding of ascetic values with economic acumen. They harnessed the tools of the age landownership, legal privilege, agrarian labor, and trade to create a self-sustaining monastic society. The innovations and strategies they adopted prefigured developments in later monastic economies and even offer insights to economic historians about pre-modern institutional management. The legacy of this period remains evident in the enduring prosperity and self-governance of Mount Athos, which, over a millennium later, continues to follow the economic rhythms set in motion during Byzantium’s golden centuries.

NOTES

- Many primary documents of Athonite monasteries typika, testaments, chrysobulls are compiled in Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents (ed. J. Thomas and A. Constantinides Hero, Dumbarton Oaks, 2000), which provides English translations. These have been used as the basis for translations of quotes herein.

- Work and Worship at the Theotokos Evergetis 1050 – 1200 [1997] by Mullett, Margaret & Kirby, Anthony or Theotokos Evergetis and Eleventh-century Monasticism: Papers of the Third Belfast Byzantine International Colloquium, 1 – 4 May 1992 (Belfast Byzantine Texts & Translations S.) [1994] by Margaret Mullett

- The 883 decree of Basil I protecting Mount Athos is recorded in the Regesten der Kaiserurkunden des Oströmischen Reiches, ed. F. Dölger, vol. 1, no. 345. It is also discussed in Harvey (1990) and Laiou & Morrisson (2007), who note its significance as an early immunity for Athos.

- John I Tzimiskes’s Athos charter (972), often called the Tragos, survives in later copies published in Actes du Prôtaton, ed. D. Papachryssanthou (Archives de l’Athos, Paris, 1975). It outlines Athos’s governance and tax exemptions.

- Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents (Dumbarton Oaks, ed. Thomas & A. Constantinides Hero) gives English translations and notes for dozens of monastic charters/typika across the 10th–13th c., documenting repeated renewals and ateleiai (fiscal exemptions) for large houses such as Patmos, Lavra, Iviron, Vatopedi, etc. Use it to locate multiple 11th–12th‑c. renewal acts with itemized taxes.

Sources (Original script)

Βίος καὶ πολιτεία Ὁσίου Ἀθανασίου τοῦ Ἀθωνίτου. In: Acta Sanctorum Novembris, vol. 3. [Greek hagiography of St. Athanasius of Athos, 10th c., original text].

Χρυσόβουλλον τοῦ 1199 (τοῦ Ἀλεξίου Γ΄) δι’ ὅ οἱ μονὴ Χελανδαρίου αὐτοδιοίκητος καὶ ἀτέλεια παραχωρεῖται. In: Сборник за народни умотворения, наука и книжнина, XXV. [Chrysobull of Alexios III for Chilandar, in Church Slavonic and Greek].

Sources (Latin transliteration or translation)

Actes de Lavra, I – II. 1970 – 1977. Archives de l’Athos, Paris: P. Lemerle et al. (Edition of documents of Great Lavra monastery, 10th – 13th c., Greek text and French summaries).

Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents. 2000. Ed. John Thomas and Angela Hero. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. (English translations of monastic typika and charters)

Regesten der Kaiserurkunden des oströmischen Reiches. 1939 –. Ed. Franz Dölger et al. Munich. (Regesta of Byzantine imperial charters; vol. 1 covers 867 – 1025, including Athos-related edicts).

Actes de Vatopédi I. Des origines à 1329 (Archives de l’Athos). Paris: Lethielleux. Diplomatic Greek texts with French résumé and commentary.

REFERENCES

ANGOLD, M., (Ed). 2006. The Cambridge History of Christianity, Vol. 5: Eastern Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (See chapter by E. Zachariadou on Athos under Ottoman rule, for context beyond 12th c.).

HARVEY, A., 1990. Economic Expansion in the Byzantine Empire, 900 – 1200. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

KAPLAN, MICHEL. 1992. Les hommes et la terre à Byzance du VIe au XIe siècle: propriété et exploitation du sol. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. (A comprehensive study of Byzantine land tenure; provides background on the status of monastic lands in our period).

LAIOU, A. E., & MORRISSON, C., 2007. The Byzantine Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

OBOLENSKY, D., 1988. Six Byzantine Portraits. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (Includes a chapter on St. Athanasius of Athos with analysis of his life and economic achievements).

PAPACHRYSSANTHOU, D., 1975. Le Protaton et les débuts de la communauté monastique d’Athos. Thessaloniki. (Historical study of the early Athos community; publishes key texts like the Tzimiskes typikon).

SMYRLIS, K., 2002. The Management of Monastic Estates: The Evidence of the Typika. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 56, pp. 245 – 261. (Examines how various Byzantine monastic foundation rules regulated estate administration).

SPEAKE, G., 2014. Mount Athos: Renewal in Paradise. Limni: Denise Harvey. (General history of Athos; useful for context and continuity of Athonite economic practices).

TALBOT, A.-M., & ALEXAKIS, A, (Eds.) 2016. Holy Men of Mount Athos (DOML Vol. 40). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Includes translations of Athonite saints’ lives which touch on economic matters, e.g. miracles of food multiplication).

ZACHARIADOU, E., 1996. Mount Athos and the Byzantine Empires (11th – 15th c.) in Αθωνικά Σύμμεικτα, no. 5, pp. 17 – 44. (Historical overview of Athos’s relations with Byzantine state; discusses privileges and imperial policies).

STOURAITIS (Ed.) 2022. The Dēmosia, the Emperor and the Common Good: Byzantine Ideas Regarding Taxation and Public Wealth (11th – 12th c.)” for the legal ideological framework and criticism of imperial fiscal practice under the Komnenoi/Angeloi.

Dr. Radostin Vazov, Assoc. Prof.

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3322-7060

WoS Researcher ID: AAY-5192-2021

University of National and World Economy

E-mail: radostin.vazov@unwe.bg

>> Изтеглете статията в PDF <<